Gabriel Collins, The Diplomat, 5 November 2015

The work of Chinese civil courts on business cases may be gradually creating a foundation for individual rights.

China’s leaders are keen historians, particularly when it comes to events that drained political power from authoritarian rulers. The Magna Carta, which established for the first time the principle that all, including the king, were subject to legal restraints on the exercise of power, is one such event. This marked a pivotal moment in world history and the document’s message still clearly disturbs China’s leaders more than 800 years after its issuance. Indeed, consider the abrupt and unexplained cancellation of a public display of one of the actual surviving Magna Carta originals at Renmin University in early October 2015. To that end, the Party leaders seek to forestall a Chinese “Magna Carta Moment,” in part by curtailing the activities of China’s rights lawyers (“weiquan lushi”), who seek to uphold the rights of individuals against the arbitrary or improper exercise of state power.

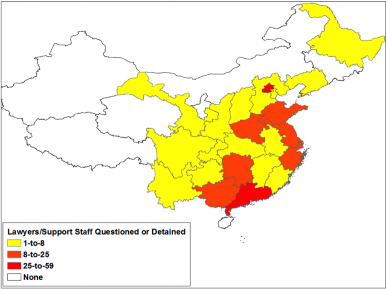

In Beijing’s mind, allowing these lawyers to operate freely could risk eventually establishing a new social contract under which the power of the Party should be subjugated to the force of an independent rule of law. Governments naturally seek to minimize potential constraints on their exercise of power. And this is precisely why Beijing is striking hard against the rights lawyers. In July and August of 2015, police interrogated and/or detained nearly 300 rights lawyers and their support staff, across 24 provinces and administrative areas. Beijing led the way, with 17 persons detained and 42 others interrogated and/or travel restricted (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: China Rights Lawyer Detention Map (July 2015- 2 October 2015)

Source: China Human Rights Lawyers Concern Group, Author’s analysis

In short, the current crackdown reflects Beijing’s deep-seated fear that rule of law could become a rallying point for broader collective action against the power of the Party State. The July 2015 stock market plunge may also be amplifying the desire of President Xi Jinping and his inner circle to curtail rights lawyering. Judicial decisions that better define individuals’ rights vis-à-vis the state could eventually coalesce into another macro force which, like financial markets, can become too powerful for the government to easily manipulate.

The government’s attempts to break and discredit the rights lawyering movement reflect a deep, palpable fear that rule of law could eventually supplant the “rule by man” which has characterized China’s political system for millennia. The country has a long bureaucratic tradition under which day-to-day activities were governed by laws and codes. Yet decisions at the top of the political structure derived legitimacy from the “Mandate of Heaven.” Chinese emperors were never constrained by a body of law the way that England’s rulers were subject to the Magna Carta or the way many modern leaders must yield to the national constitution and court system. The Communist Party operates in a similar fashion, with the Party effectively existing “above the law.” Indeed, recent clarifications to CPC internal discipline procedures explicitly highlight the need to keep Party rules distinct from the “regular” Chinese legal system.

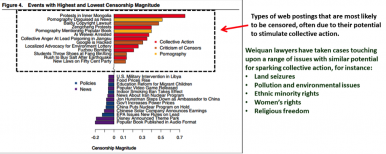

Beijing’s fear of rights lawyers also shares a common trait with China’s vast Internet censorship program: the desire to suppress and constrain any type of activities which could spark collective action. Unsurprisingly, there are not any official statements which clearly state the motivations for detaining weiquan lawyers. Nonetheless, an innovative study of China’s internet censorship program by Professor Gary King and his research team at Harvard University sheds light on the matter. During the first half of 2011, King and his team downloaded social media posts from nearly 1,400 Chinese websites, ultimately collecting and analyzing more than 11 million discrete posts.

What King and his team found was striking: The most highly censored events were not criticisms of the Chinese government, but rather, events or ideas that had a high potential for stimulating group formation or collective action. For instance, posts about protests in Inner Mongolia, protests by angry migrant workers in Zengcheng, and anger about local lead poisoning of children in Jiangsu were intensively censored (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2: Conceptual Relationship Between Internet Censorship and Repression of Rights Lawyers

Source: King et. al., Author’s Analysis

King’s groundbreaking research provides illuminating context as to why the Chinese government is cracking down on the rights lawyers. These lawyers are not “traditional” run-of-the-mill dissidents. Rather, they are much more dangerous in Beijing’s eyes because they not only fight for principles, but are clever advocates who (1) use the law, an institution that transcends their personal views and can yield a concrete, precedent-setting outcome and (2) are often skilled at organizing and rallying support, and (3) they receive significant – and likely increasing – attention in Chinese society.

Click here for Full text