Key Takeaways:

–Over the past two years, gasoline output at Sinopec and CNPC/PetroChina has surged relative to diesel fuel, reaching a new high of 0.71 barrels of gasoline produced for each barrel of diesel fuel. This is primarily a result of surging passenger car sales and stagnating industrial demand for diesel fuel.

–Our data analysis of the past four years of car sales and gasoline consumption levels suggests each million new cars sold will add 10.5-to-13 kbd of annualized gasoline demand.

–A serious economic slump could knock this down to 5-to-7 kbd of incremental gasoline consumption per million new cars sold.

–In 2014 and 2015, we project that Chinese drivers will add 220-to-250 kbd of new gasoline demand each year.

China’s legion of passenger car owners—280 million of them at year-end 2013 according to the Ministry of Public Security—cannot by themselves salvage the currently weak global oil demand picture. Based on what the data show so far, gasoline demand should rise by approximately 10% year-on-year in 2014.

This represents an increase of ~220 kbd, equivalent to ~500 kbd of incremental crude oil demand—roughly the amount China has been injecting into its strategic petroleum reserve earlier in the year. But even this respectable growth cannot make up for stagnant demand for diesel fuel—China’s industrial mainstay liquid energy source. Slower trucking activity substantially crimps fuel demand because one working industrial truck likely uses as much fuel as 5-10 passenger cars.

Over the past four years, China’s two largest refiners, Sinopec and PetroChina, have substantially increased gasoline production relative to diesel production in their plants. There are other refiners in China, but Sinopec and PetroChina account for more than 80% of the country’s gasoline output. Furthermore, China’s refined product imports and exports are de minimis relative to overall demand, so the product output slate from the “Big 2” refiners is a good proxy for assessing how demand for gasoline, diesel, and other products are shifting relative to each other.

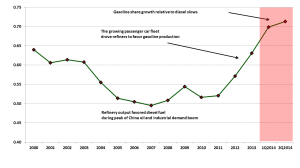

Over the past two years, gasoline output at Sinopec and CNPC/PetroChina has surged relative to diesel fuel, reaching a new high of 0.71 barrels of gasoline produced for each barrel of diesel fuel (Exhibit 1). This is primarily a result of surging passenger car sales and stagnating industrial demand for diesel fuel, a dynamic discussed further below.

Exhibit 1: Sinopec and CNPC Gasoline/Diesel Production Ratio

Barrels of gasoline per barrel of diesel produced

Source: Company Reports, China SignPost™ analysis

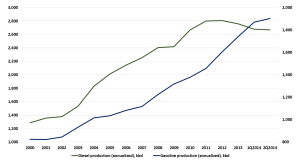

Three core dynamics grab our attention as we assess the China gasoline situation. First and foremost, refiners’ decision to favor gasoline output at some level reflects weakness in China’s industrial economy, where trucking drives diesel demand. Unlike the U.S., with its well-developed intermodal logistic system, China’s consumer economy relies much more heavily on trucks to move goods, as the railroad system primarily moves coal and other bulk commodities. The Big 2 refiners’ diesel and gasoline production trends over the past 2 years reflect stagnation in diesel demand and strong growth in gasoline consumption in China, albeit with flattening in recent months (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2: Sinopec and CNPC Gasoline and Diesel Fuel Production Volumes, Kbd

Diesel fuel production on left vertical axis, gasoline production on right vertical axis

Source: Company Reports, China SignPost™ analysis

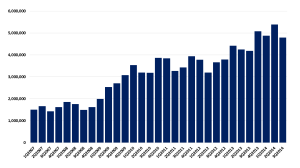

Second, China’s car fleet continues expanding rapidly, but many cars are not being driven as much as refiners and crude oil suppliers might hope. New car sales are still growing strongly in relative terms (although sales have slowed a bit recently) and dealers sell massive numbers of new cars each quarter—nearly 4.8 million in 3Q2014 alone (Exhibit 3).

New car sales give solid insights into how China’s overall passenger car fleet is expanding, since the real explosion in sales began slightly over five years ago, meaning that the burgeoning number of cars that have entered the fleet during the recent car buying spree still have many years of service left in them, scrapping rates are very low, and the relationship between new cars sold and the number of cars entering the vehicle fleet on a net basis is much closer to one-to-one than it would be in a more mature market.

Exhibit 3: Sales of New Passenger Cars in China, by Quarter

Units sold

Source: CAAM

Car Usage Not As Intense as In Other Markets

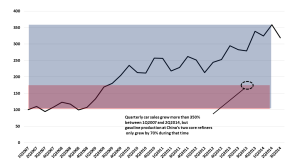

To look at the new car sales data from a different angle, consider that between the first quarter of 2007 and second quarter of 2014 (the latest period for which the Big 2 have reported gasoline production), the number of cars sold per quarter grew by more than 350%, while Big 2 gasoline output only rose by 70% (Exhibit 4). Taken in conjunction with the slowing increase in the gasoline/diesel ratio shown in Exhibit 1, the data in Exhibit 3 suggest lots of cars are being sold, but that they are mostly prestige items that sit in garages and driveways and do not see much pavement time. It also suggests that China is not developing a strong long-distance car travel culture like that which exists in the U.S., for instance. The country is investing heavily in adding and expanding highways between cities, but by the looks of gasoline demand, these investments are likely not promoting a groundswell increase in inter-city car travel.

Exhibit 4: China Car Sales Have Grown Several Times Faster Than Gasoline Sales Since 2007

Source: CAAM, Company Reports, China SignPost™ analysis

Chinese drivers are much less sensitive to fuel price changes than their American peers. There are two core reasons for this. First, Chinese car buyers tend to be much more affluent in relative terms than car buyers in the U.S., where a lack of public transportation makes private car ownership a necessity even for impoverished citizens in many areas. Second, with China’s notorious traffic jams, congestion is a much stronger influencer of car use than pump prices. Improved infrastructure and traffic management policies that restore traffic flow would do much more to stimulate increased car use in China than lower gasoline prices ever could, since even free gasoline is not helpful if the road subjects drivers to the frustration of gridlock.

Implications

Ultimately, we expect China’s passenger car fleet to continue growing at a slower, but robust rate for at least 2-3 more years, but it will not deliver a market-saving oil demand growth bonanza. Gasoline demand growth will be respectable, it just will not support the market-shaking oil hunger that characterized much of the 2004-12 period in China. Jammed up urban areas will thwart greater car use and inter-city travel for the bulk of Chinese largely remains a game of buses, trains, and planes—not personal cars. Each Lunar New Year features hordes at train stations, long lines at bus stops, and angry flyers in crowded airports. Yet images of jammed expressways between cities (reminiscent of U.S. Interstates during holidays—Boston to New York on I-95 or I-84, anyone?) remain conspicuously absent.

China’s gasoline demand—and by extension, need for crude oil—will continue to grow meaningfully as auto dealers work to penetrate 3rd, 4th and 5th Tier markets. Our data analysis of the past four years of car sales and gasoline consumption levels suggests each million new cars sold will add 10.5-to-13 kbd of gasoline demand.

This time period is, in our mind sufficient—coupled with our in-depth analysis of Chinese passenger car owners’ driver behavior—to make us comfortable providing this shorthand metric for assessing how car sales will likely translate into incremental gasoline demand. The biggest upside risk to our view is that as China’s used car market grows and rural car ownership creeps up, rural drivers may drive more miles than their city cousins and thus help bump up the incremental fuel demand benchmark.

Because the biggest “bulge” in the car boom came in 2009, there are likely at least five more years before fleet retirements began to slightly erode the positive impact new car sales have on gasoline demand. For 2014 and 2015, we project that Chinese drivers will add 220-to-250 kbd of new gasoline demand annually.