Chinese consumers’ growing appetite for meat is driving increased grain imports, which is great news for corn and soybean growers in Argentina and Brazil. Yet Chinese agriculture and investment companies’ interest in the pampas and cerrado are not universally welcome, and Buenos Aires and Brasilia have both promulgated laws restricting foreign land ownership.

Argentina’s Law on Rural Lands, which passed the upper house of parliament by a vote of 62-1 in December 2011, caps foreign ownership at 15% of the country’s total arable land area. For reference, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that foreigners currently own approximately 10% of the country’s arable land. The new law also sets a ceiling of 1,000 hectares per individual plot of land owned by a foreign entity and calls on the government to create an inter-ministerial national land registry to keep tabs on who owns what pieces of land.

In 2010, Brazil’s Attorney General responded to concerns driven in part by fears that Chinese investors wanted to purchase major chunks of land in Brazil’s interior by re-interpreting a 1971 land ownership law in a way that would prohibit foreign entities from owning more than 25% of any municipality or possessing more than 100 “modules” of land, which can vary from 100 to 10,000 hectares in size (Reuters).

Chinese investors will continue pursuing agricultural investment opportunities in Latin America

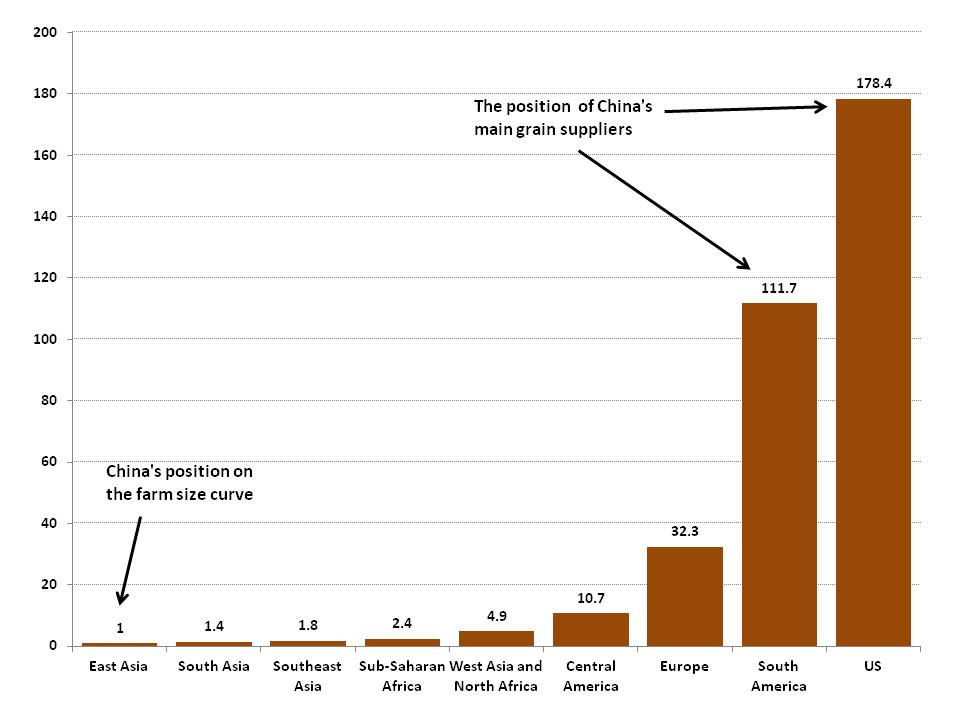

Reason 1: Chinese farmers cannot achieve the production efficiencies of their foreign peers. Chinese farms are much smaller on average than those in key grain producing regions like the U.S., Latin America, Russia, Australia, and Ukraine.

Size matters in the farming world and the economies of scale that an average farmer working nearly 280 hectares in the U.S. and 112 hectares in South America are simply unattainable for their Chinese counterpart, who typically grows crops on a mean size of 1 hectare (Exhibit 1).

In practice, this suggests that even the larger Chinese grain farms will be much smaller and more manpower-intensive than a Midwestern U.S. farming operation that may be nearly 1,000 hectares in size and achieves a wage cost-to-acreage ratio that Chinese farms will find hard to match, especially as wage inflation continues.

Exhibit 1: Mean size of Chinese farms versus those of other regions

Hectares per farm

Source: World Bank, China SignPost™

In addition, China already uses nearly all of its arable land that is suitable for cultivating corn, soybeans, rice, and wheat. World Bank data show that located within six hours of market there are more than 53 million hectares of land available for additional cultivation of soybeans, corn, and wheat in Argentina and Brazil—62 times the amount of land area available for expanding production of these three grains in China.

The lack of room for farm expansion helps set the stage for additional increases in China’s grain imports and will also help drive ambitious Chinese agriculture companies to seek opportunities abroad to boost their production. China is already the world’s largest soybean importer and is on the cusp of becoming one of the world’s larger corn importers as well.

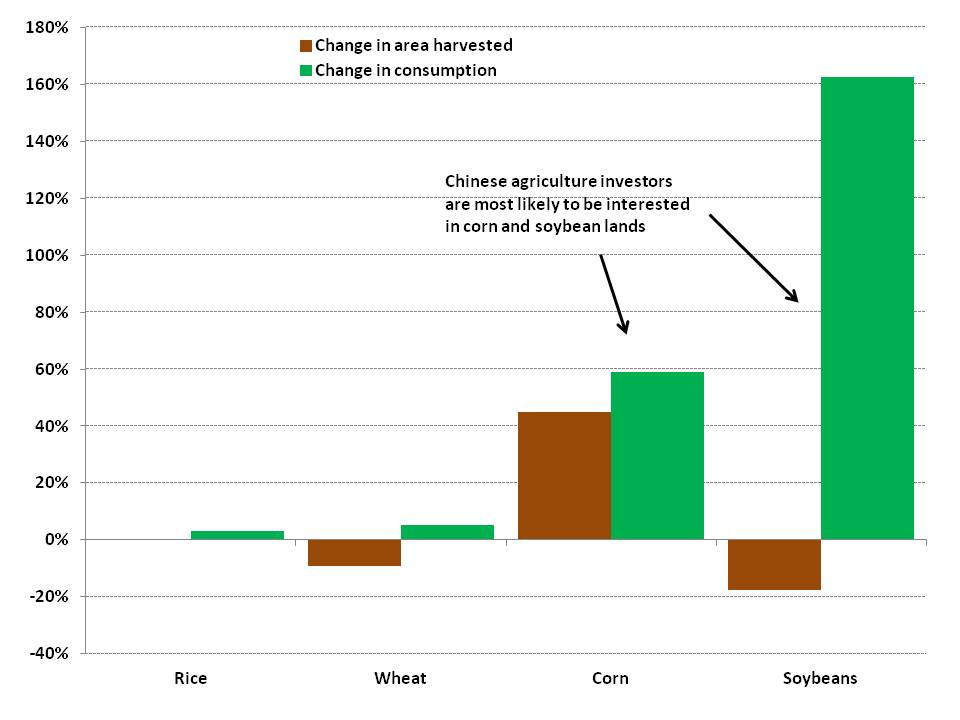

With such a robust market to serve, Chinese agriculture investors looking for projects abroad will likely continue prioritizing areas suitable for growing soybeans and corn, as Chongqing Grain Group is looking to do in Brazil with its planned soybean production, storage, and processing project.

Between 2000 and 2011, China’s consumption of soybeans rose by more than 160% while the area harvested of soybeans within China actually declined by nearly 20% during that same period (Exhibit 2).

Corn consumption in China rose by nearly 60% between 2000 and 2011, while the area harvested rose by roughly 44%. Soybean yields in China rose by 6.6% between 2000 and 2011 while corn yields increased by 25%. The consistent trend of Chinese grain consumption growth substantially exceeding the increase in area harvested and yield increases provides yet another signal of increasing reliance on imported grain supplies in coming years and a commensurate likelihood that pre-occupation with grain supply security will continue.

Exhibit 2: Change in Demand for Corn and Soybeans vs. Growth in Area Harvested (2000-2011)

Source: USDA, China SignPost™

China’s lagging grain yields are in part a product of small farms that are a legacy of the Communist Party’s insistence that each rural family be allotted a small plot of land. Political reforms may enhance farm efficiency, but are unlikely to allow large-scale consolidation in land ownership that would be necessary to permit industrial farming seen in the U.S., Latin America, and Eastern Europe. Even if more radical rural land ownership reforms were allowed, rising consumer demand would likely outstrip farmers’ efficiency gains.

Clean water supplies are also increasingly a constraint on China’s ability to boost production of staple grains and by importing more foreign grain, China is effectively importing water that can then be re-allocated to growing industries, cities, and other pressing needs.

Reason 2: Brazil and Argentina offer a combination of relatively clear land ownership laws, an established farming support sector (equipment, seed, chemicals), decent infrastructure for moving produce to market, and significant reserves of additional land for growing the staple grains China’s consumers increasingly need.

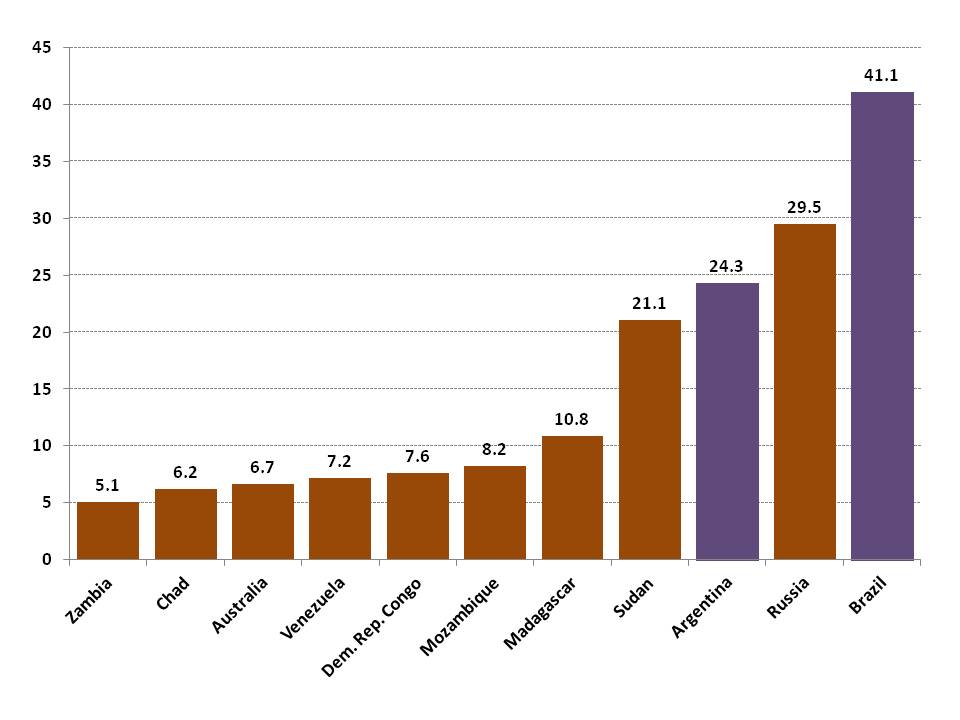

Chinese farm investors looking for opportunities abroad will go where the land is. Of the 10 countries with the largest available land base located within 6 hours of market and available for rain-fed grain, sugarcane, and oil palm cultivation, Brazil is number one (41.1 million hectares) and Argentina is number three (24.3 million hectares), respectively (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3: Available Arable Land Base for Corn, Soybeans, Wheat, Oil Palm, and Sugarcane

Million hectares, located within 6 hours or less from market

Source: World Bank, China SignPost™

The potential farmland base is dominated by lands suitable for growing soybeans, corn, and wheat—precisely the grains China is seeing the highest demand growth for and that Chinese investors are most interested in.

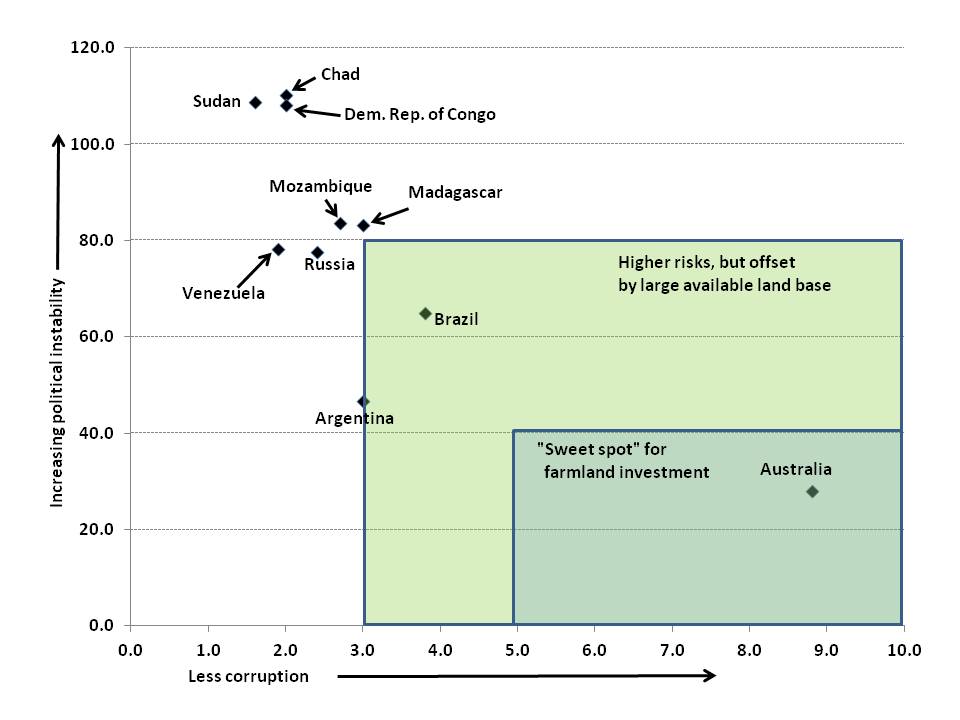

Among the 10 countries with the highest farmland availability (Exhibit 4), Argentina and Brazil score better in terms of state stability and have lower levels of corruption than all the other countries except for Australia. Admittedly, these are relative, not absolute, advantages, as both nations still suffer from significant bureaucratic inefficiency and corruption. But even with the recent tightening of legal regulations governing foreign ownership of agricultural lands, Argentina and Brazil still offer comprehensively better investment opportunities than competing areas in Africa, for instance.

Exhibit 4: State Stability and Corruption Ratings for Brazil and Argentina Compared to the Other Top 10 Prospective Agricultural Investment Destinations

Source: Transparency International, Foreign Policy, China SignPost™

Potential Strategies Chinese Investors Can Use Moving Forward

Agriculture investments are often more politically complicated than mining or oil & gas projects because foreign investors are often inserting themselves directly in the middle of a people’s relationship with its government and the land it lives on. Oil wells and copper mines are usually not as personal and visceral an issue with citizens as food crops and land ownership are.

The Argentine and Brazilian governments’ decisions to tighten the reins regarding foreign ownership of agricultural lands reflects such sensitive politics, but by no means rules out opportunities for intrepid investors. Chinese asset hunters feel the drive of the country’s growing demand for grains and in a number of cases, also offer investors such as China Investment Corporation a chance to put capital to work in a way that would potentially pay rich dividends for national food security. Below are some of the more likely scenarios we see, some of which are emerging already.

1) Enter into long-term leases for farmland. This sidesteps restrictions on foreign farmland ownership while still allowing the lessee to keep control of the products produced on the land. Heilongjiang Beidahuang Nongken is pursuing this type of strategy with its plan to invest US$1.5 billion in developing farms and supporting infrastructure on 300,000 hectares of land in Rio Negro province in Southern Argentina in exchange for the rights to grow a range of grains and vegetables and export them to China over a 20-year period.

2) Chinese investors can take minority stakes in foreign farming projects. Ultimately, grain markets are global and even if every kernel grown on a Chinese invested farm stays in the producing country’s local market, it helps free up grain from other farms that can then move into the export market and potentially be shipped to China. Chinese oil companies have quickly cottoned on to this reality with their foreign oil investments and corresponding benefits for everyone in the market.

There is currently no reason why Chinese grain farmers investing in projects abroad would not also follow such a purely-commercially-focused model. Minority stakes are also politically simpler to obtain, since even the restrictive new land ownership law in Argentina leaves room in its wording that suggests continued openness to foreign investors taking non-controlling stakes in farm projects.

3) “Loans for Grain.” Since 2008, Chinese banks have loaned at least US$60 billion to oil producers Venezuela, Brazil, and Ecuador in exchange for oil supplies of at least 690 thousand bbl per day—roughly 12% of China’s February 2012 crude oil imports. A loans for grain approach holds promise, particularly since each unit of currency loaned to a grain producer would have a larger impact on China’s grain supply security because on balance, staple grain imports (corn, soybeans, wheat) are still a much lower proportion of total consumption than is the case for oil, where China now imports more than 50% of its needs.

4) Create local agricultural operating companies backed by Chinese capital, staff them with locals. Such companies would be the vehicles used to purchase or rent and then operate farmland in Brazil and Argentina. The local employment, taxes, and links with the communities that this model would generate would help alleviate the political suspicions that are fueling xenophobic land ownership laws in the first place. If grain for export to China is an important concern for Chinese investors in the company, they could structure right-of-first-refusal supply agreements that would give them priority in the event they needed grain for shipment to China, but would still retain flexibility to market the grain elsewhere as market conditions ebb and flow.