Executive Summary

–China’s annual trade with Latin American countries is now worth at least US$118 billion per year, nearly 12 times larger than what it was in 2000. This makes China’s trade with Latin America roughly the same size as its growing trade with Africa, a region whose ties with China receive much attention.

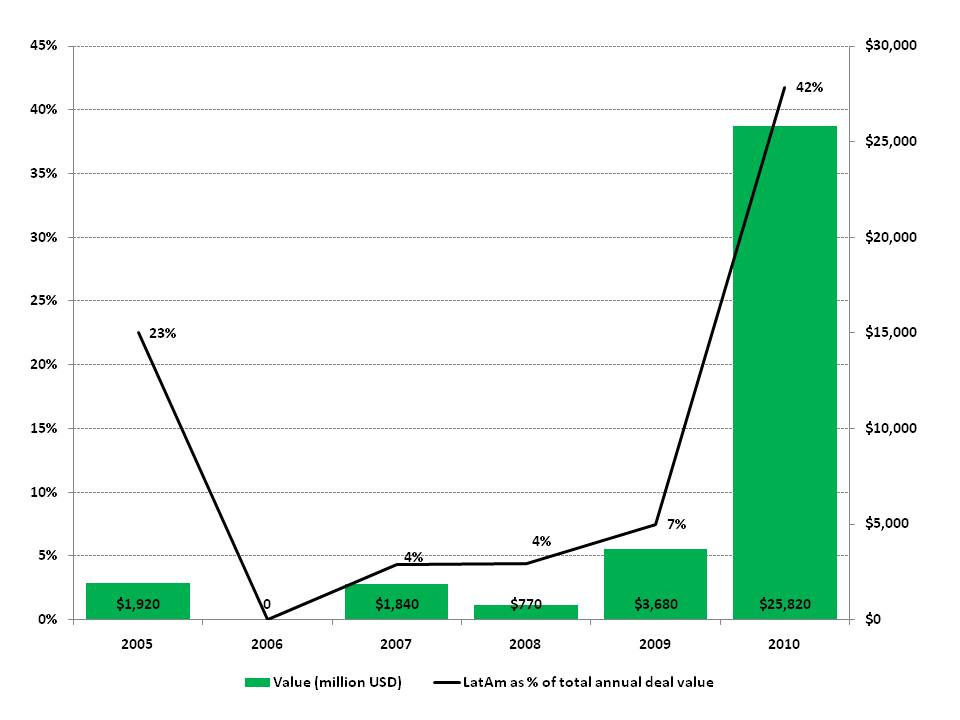

–Chinese companies made investments in a range of Latin American energy, mining, agricultural, industrial, and financial assets worth more than U.S.$25 billion in 2010, a watershed year that saw Latin America account for more than 40% of China’s large overseas investment deals, based on China Global Investment Tracker data.

–China’s natural resource-focused investment in Latin America will continue, but is also likely to diversify into local manufacturing as well as retail and other consumer-oriented businesses.

–China’s relations with Latin American countries are driven primarily by economics and a bit by politics, mainly the desire to isolate Taiwan. China sees soybeans, oil, iron ore, and burgeoning local consumer markets as the prize and will use its growing leverage to secure better economic terms, not force Latin countries to do its political bidding. Beijing does not want to overly irritate Washington, its most important foreign relationship.

In assessing the potential strategic realignments of China’s growing economic presence in Latin America, we believe it is important to examine both trade and investment, since both influence bilateral diplomatic relationships and because investment often follows in the footsteps of China’s rapidly growing trading relationships, which to date have been heavily focused on natural resources.

As continuing U.S. economic weakness fuels perceptions that Washington’s global influence is declining, many countries in Latin America are enjoying vibrant economic expansion driven by China’s hunger for natural resources. During this boom, China’s trade with Latin America has grown from US$10 billion in 2000 to nearly US$120 billion in 2009 (IMF). In reality, discussing China’s trade and investment ties in Latin America means primarily its economic relationships with Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, Chile, Venezuela, and Peru.

As China’s outbound foreign investment rises, Latin America is a popular destination. Indeed, data from the Heritage Foundation’s China Global Investment Tracker show that 42% of China’s large foreign investments by value in 2010 were in Latin America (Exhibit 1). These deals were worth more than US$25 billion, which is far less than U.S. foreign direct investment in the region, but certainly sufficient to show that Latin American countries can now choose from among a range of potential investors. We believe this dataset is particularly valuable because most sources simply show money flows from China into the region, most of which end up in offshore financial havens such as the Cayman Islands. In contrast, the data we are working with show the real deals in which Chinese firms build auto plants and buy stakes in oil, copper, and farming projects.

Exhibit 1: China’s Large Foreign Investments in Latin America

Billion USD and percentage of total overseas large investments in a given year

Source: The Heritage Foundation, China SignPost™

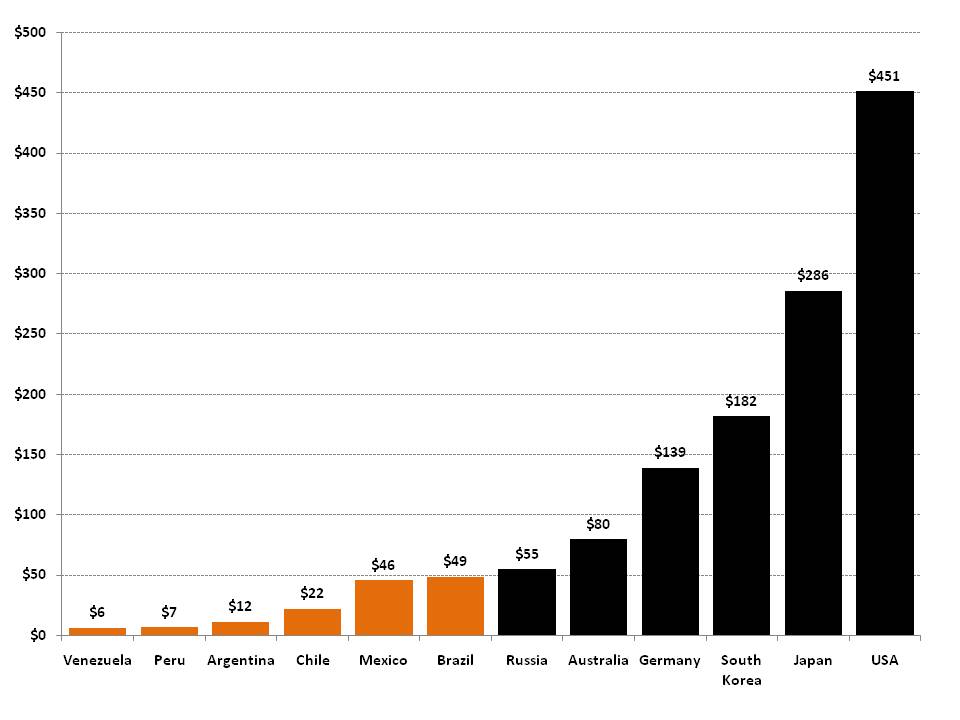

While growth in trade volumes has been rapid, China’s trade with its largest Latin American trading partners pales in comparison to its trade with the U.S., Japan, and Northern Hemisphere powers. To put the dollar amounts in perspective, China’s trade with Brazil was just under US$50 billion in 2010; while its trade with the U.S. was US$451 billion—more than three times larger than its total trade with its 6 largest Latin American trade partners (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2: China’s Latin American Economic Relationships in Perspective

Sum of imports from, and exports to, China (billion USD)

Source: CIA World Factbook (2011), China SignPost™

Chinese investors are acquiring a range of assets including mines, farms, and oilfields in Latin America, as well as seeking opportunities in growing consumer economies in countries such as Brazil, Argentina, and Peru. We believe the vast majority of China’s interactions with Latin America are driven by economics. The remainder is primarily political—namely, efforts to isolate Taiwan diplomatically.

For example, Chinese companies are unlikely to make significant profits by investing in places like Paraguay, Guatemala, and Belize, but swaying these governments to recognize Beijing rather than Taipei would be a huge step in the PRC’s campaign to reduce further from 23 the number of sovereign states that still recognize Taiwan diplomatically—the vast majority of which are located in Central and South America and the Caribbean Community (Belize, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines).

Among China’s main Latin economic partners, the government of Venezuela and to a lesser extent Argentina often takes anti-American policy positions, but we believe Beijing’s main objective is to use the relationship to help ensure its grain and oil supplies, while not seeking deliberately to offend the U.S., China’s most important foreign relationship for decades to come.

China has limited military-to-military interaction and arms sales in Latin America, but these are small in scope and are not a major part of China’s Latin American relationships at present. China is certainly monitoring local developments closely and may try to market more sophisticated weapons in Latin America—particularly systems such as the J-10 fighter or trainer aircraft once AVIC can independently mass produce the requisite jet engines and export aircraft independent of Russia. However, we do not believe closer military ties are anywhere near the top of Beijing’s Latin America agenda because they would likely seriously irritate the Pentagon and potentially harm China’s ties with the U.S. without yielding corresponding benefits for Beijing.

Economic Ties

Broadly speaking, Chinese investors and traders come to Latin America because it offers a wealth of exportable minerals and agricultural products that China needs urgently to fuel its continuing manufacturing boom. The more populous Latin American countries—especially Brazil, Argentina, Peru, and Chile—also have rapidly growing domestic markets with consumers hungry for cars, televisions, air conditioners, and other goods that Chinese firms can either supply from China or manufacture locally, as in the case of Chery’s car factory in Uruguay.

In 2010 alone, Chinese firms invested around US$15 billion in Latin America, 9% of the annual total, according to CEPAL. Much of this activity came from major corporate mergers and acquisitions, including the Repsol YPF-Sinopec and Bridas-CNOOC deals (Argentina). Last year was notable in that it featured a massive increase in non-financial Chinese investment in the region. As in prior years, much Chinese “foreign direct investment (FDI)” to the Latin America/Caribbean region came in the form of capital flows to offshore financial havens, as opposed to investments in real producing assets.

As the U.S. continues to struggle with sluggish growth and debt-related problems, we believe Latin America will gain attractiveness as a place for China’s state-owned companies and banks to put capital to work and diversify their portfolios to hedge against continued political and economic risk in U.S. assets. In practical terms, this means we are likely to see more Chinese purchases of hard assets in the region in coming years, particularly if commodity prices decline for a more than a few weeks at a time.

Risks and Opportunities in Relations between China and its Latin Trade Partners

–Managing divergent perceptions of China between elites and the common people, who may not see the same direct benefits from Chinese trade and investment. It is also increasingly likely that a divergence in perceptions of China will emerge as it has elsewhere in the developing world: between economic elites who oversee the commodity exports and the majority of the population, whose professions in many cases may be negatively affected by competition from Chinese goods and expat workers. In essence, the owners of mines or soybean farms are likely to see China as a cash cow, while the thousands of retail traders on the streets of Lima or factory owners in São Paulo or Buenos Aires may have far more negative feelings. In countries with populist democracies, such sentiments could greatly complicate their high-level diplomatic and commercial relations with Beijing.

–Potential for emergence of stronger anti-Chinese sentiments amongst the populace. China’s rising economic presence in the region, and in particular, competition between Chinese goods and local manufacturing in countries already struggling with poverty and unemployment are likely to become major friction points. Based on our research, and a recent two-month stay by one of the authors in Argentina, we think that very few local manufacturing companies will be able to compete head-to-head with products imported from China; or for that matter, with locally-based companies run by immigrants from China. The feeling that Chinese migrants are “stealing” local jobs could be a powerful driver of xenophobia such as that which has been directed against Chinese expatriates in Africa, the South Pacific, and Southeast Asia over the past 15 years. The first stage of China’s economic engagement with Latin America entailed the purchase of natural resources at arm’s length, but the second stage of the trade boom that is now unfolding involves the increasing penetration of Chinese businesses into local markets, with the attendant risk of sparking political frictions, and in the worst case, street level violence between Chinese merchants and disgruntled locals. U.S. influence in the region is deeply resented, but typically triggers a much less visceral reaction than would a competing Chinese vendor located in the stall next to a locally-owned kiosk that also sells clothing and shoes—but at a few centavos less per item and thereby “stealing away” customers.

–African precedents. Latin Americans should carefully consider the experiences of China’s African commodity suppliers, particularly Angola. In a recent expose, The Economist notes that the China International Fund, which it terms the “Queensway Syndicate,” has secured oil and mineral deals worth billions of dollar in Angola, Guinea, and other African countries, but thus far has “failed to meet many of the obligations it took on to win mining licences.” In Angola, for example, the syndicate is alleged to have stopped funding the projects it promised to support—such as the Benguela railway project—in order to force the Angolan government, which staked substantial political legitimacy on infrastructure building, to fund the projects. Insulated by payments to offshore accounts, the syndicate was able to continue exporting oil, likely at a substantial markup, and reaping large profits at the expense of the Angolan people (Economist). Likewise, in Latin America there is a real possibility that promised Chinese-backed investment projects may not come to pass, particularly those implicitly or explicitly tied to resource deals.

–Protection of local workforces. Latin American governments are likely to assess Chinese investments more closely and set stricter standards to ensure local employment and make sure as much value-added activity as possible remains on their side of the Pacific.

–Farmland ownership is also becoming a highly sensitive issue. For example, Argentina’s Congress is currently considering a new bill regarding a “Law of Protection of the National Domain over the Property, Possession or Holding of Rural Lands” (Baker McKenzie). In this bill, foreigners would be able to own no more than 20% of Argentina’s farmland and individual persons or entities would not be able to purchase more than 1,000 hectares. While the law is still being debated and has many loopholes (such as the fact that it does not appear to restrict foreigners’ ability to lease farmland), the apparent seriousness with which it is being considered suggests a more xenophobic shift in land control policies in Latin America.

–Can Chinese firms be trusted to build safe infrastructure? In addition, the deadly July 2011 Wenzhou train crash has put a serious dent in foreign perceptions of how well Chinese firms can build safe, high-quality infrastructure. Infrastructure projects constitute a substantial part of China’s investment portfolio across Latin America and the country’s firms will likely face a harder sell in coming years convincing customers that they have identified and overcome safety challenges. At the same time, a number of countries in the region need significant infrastructure improvements, leaving room for Chinese firms to pitch for business despite the Wenzhou tragedy. Brazil, in particular, needs foreign investment in its infrastructure badly as it faces major time pressures in upgrading its transport and power systems in preparation for the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio and to enable future economic growth. FIESP (Industrial Federation of São Paulo) estimates that from 2012 on, the rail sector will account for 29% of Brazilian infrastructure investment and power 44% of infrastructure investment.

–Can the region handle a prolonged commodity price decline if Chinese growth slows more than expected? A sustained downturn in commodity prices that could come from slower Chinese and global economic growth might quickly lay bare economic fault lines that have so far remained covered due to high and growing commodity cash flows into economies like Brazil, Peru, and Argentina.