–In late February 2011, the National People’s Congress ratified an amendment to China’s Criminal Law that makes it illegal for PRC nationals and companies to bribe foreign government officials or officials of non-governmental organizations.

–The amendment, which became effective on 1 May 2011, is the first step in a long and complex process, but nonetheless sets a welcome precedent by implicitly recognizing that bribery abroad is destructive to Chinese interests.

–The rapid penetration of smartphones and other forms of Internet connectivity in the developing world provide opportunities for common citizens to help enforce the laws by independently reporting graft involving Chinese business activities in their country.

–The efforts of the Janaagraha Centre for Citizenship and Democracy and its new IPaidABribe.com bribe reporting website offer a shining example of how technology can be harnessed to improve transparency and fight graft.

–IPaidABribe.com, which went live in fall 2010, has so far garnered more than 436,000 hits and over 8,400 reports discussing bribes paid.

Thus far, China’s lack of anti-bribery mechanisms that apply to companies operating abroad like the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) has been a major competitive advantage for Chinese businessmen competing overseas against foreign firms, which must often adhere to strict laws at home forbidding graft in corporate activities abroad. Yet a recent development suggests Beijing is increasing its commitment to reduce bribery by Chinese firms and individuals doing business overseas.

In late February 2011, the National People’s Congress ratified a set of 49 amendments to China’s Criminal Law, one of which makes it illegal for PRC nationals and companies to bribe foreign government officials or officials of non-governmental organizations (为谋取不正当商业利益,给予外国公职人员或者国际公共组织官员以财物的, 依照前款的规定处罚). The amendment, which became effective on 1 May 2011, is the first step in a long and complex process, but nonetheless sets a welcome precedent by implicitly recognizing that bribery abroad is destructive to Chinese national interests. It also suggests that Beijing realizes Chinese firms’ growing overseas economic presence has created new corporate risk management issues that need to be addressed by an evolving body of laws—among them, stronger provisions against bribery of public officials overseas.

Large loopholes remain—for example, the fact that bribing business partners other than government or NGO officials is still not explicitly criminalized—and the amendment’s vague language leaves substantial leeway for potential bribers to find ways to abide by the “letter” of the law but still sweeten the pot for government officials in ways that would not pass muster in countries such as the U.S., UK, France, Japan, and South Korea, which have all ratified the OECD Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions.

For instance, a briber could pay a private middleman, who could then “independently” transfer the funds or gift to the intended government recipient. Tightening the amendment’s language regarding intent and more concretely specifying what exactly constitutes a bribe and who is a “public official” will be essential steps to make the law an effective anti-bribery tool. More explicit language can make the law more easily enforceable and also help reduce the risk of prosecutors potentially abusing a vaguely worded legal statute to pursue anti-corruption cases driven by politics rather than legal merit. As in so many other areas, the new law faces substantial challenges from the Chinese central government’s tendency to pass detailed and often enlightened laws but then prove unable or unwilling to enforce them fully and systematically in practice.

Enforcing the new law poses major challenges because we do not expect corrupt foreign officials to suddenly begin turning in Chinese businessmen who offer bribes. It is equally unlikely that the bribers themselves will suddenly begin self-policing.

Rather, using technology to tap into civil society in places where Chinese firms make overseas investments can help enforce China’s new anti-bribery amendment. The rapid penetration of smartphones and other forms of Internet connectivity in the developing world provide opportunities for the common citizens most harmed by graft to report suspected graft by Chinese businesses and their local partners.

The efforts of the Janaagraha Centre for Citizenship and Democracy and its new IPaidABribe.com bribe reporting website offer a shining example of how technology can be harnessed to improve transparency and fight graft. IPaidaBribe.com, which went live in fall 2010, has so far received more than 436,000 hits and over 8,400 reports discussing bribes paid. According to Janaagraha, IPaidABribe.com allows citizens to anonymously report bribes they or their family and friends were forced to pay as well as instances where people resisted bribe payments or did not have to pay bribes because of good government systems or honest officials. The site’s founders seek to have this grassroots reporting on the nature, number, pattern, types, locations and frequency of actual corrupt acts and values of bribes will add up to a valuable base of knowledge that will help fight corruption.

How can citizen-based reporting initiatives like IPaidABribe.com help China enforce its new foreign anti-bribery amendment?

Technology-based initiatives for improving governance empower citizens and present opportunities to analyze relevant data in new ways and use the products of this analysis to quickly design and implement much more effective anti-corruption efforts. To be sure, challenges will arise in finding the ways to efficiently collect and analyze data while also ensuring privacy.

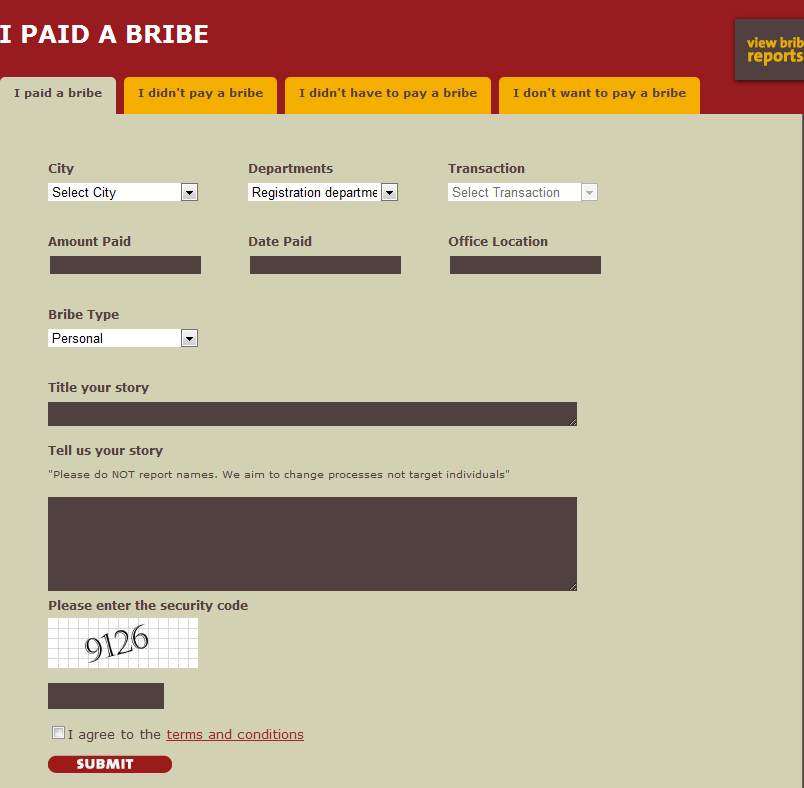

One of the most important elements is to make it possible for Chinese workers overseas as well as local citizens to use a secure website to anonymously report details of potential corrupt activities they have witnessed. Exhibit 1 (below) shows a snapshot of IPaidABribe.com’s reporting site layout, which is visually simple, captures vital details, and preserves the reporter’s anonymity, an essential step to protect him or her from possible retribution.

Exhibit 1: IPaidABribe.com reporting page layout

Source: IPaidABribe.com

The site will need to be multilingual (UN official languages: Chinese, English, French, Spanish, Russian, and Arabic) and smartphone friendly, since people without home computers may still possess advanced mobile phones. Sub-Saharan Africa already has millions of smartphone subscribers who use the devices as their main Internet access point, and smartphones could command 30-40% of the mobile phone market in the region within a few years, according to AfricaNext.

Additional vital questions are: (1) who will manage the site and (2) how to compartmentalize information if Chinese netizens begin using the site to report instances of graft within China even though the site would be focused on bribery by Chinese firms operating overseas. If Beijing chose to create a government-run bribe reporting website similar to IPaidABribe.com, users might be suspicious that their identities were not being protected properly. Business interests would also likely lobby hard to prevent the site from becoming operational or being advertised to those who might be willing to blow the whistle on bribery involving Chinese businesses abroad or at home.

A more effective set up might be for an outside non-governmental organization (NGO) such as Transparency International to operate the site, since they would be seen as a trustworthy, independent presence. Information collected on specific cases of graft could be shared with the Chinese authorities, and if an investigation were not commenced within a reasonable quiet period (perhaps 30 days), the information could then be published to pressure China’s Central Commission for Discipline Inspection or other enforcement bodies to take action against suspected bribers. Even if these methods proved too proactive bureaucratically or too sensitive politically, it might be possible to implement more subtle or otherwise modified versions of this process—though they might be less effective in critical respects.