China SignPost analyzed the data for U.S. exports to China by state from the 2010 U.S. Exports to China by State report from the U.S.-China Business Council. The results shed light on both how strongly U.S. exports to China have grown in the past 10 years and how regionally diverse they are becoming.

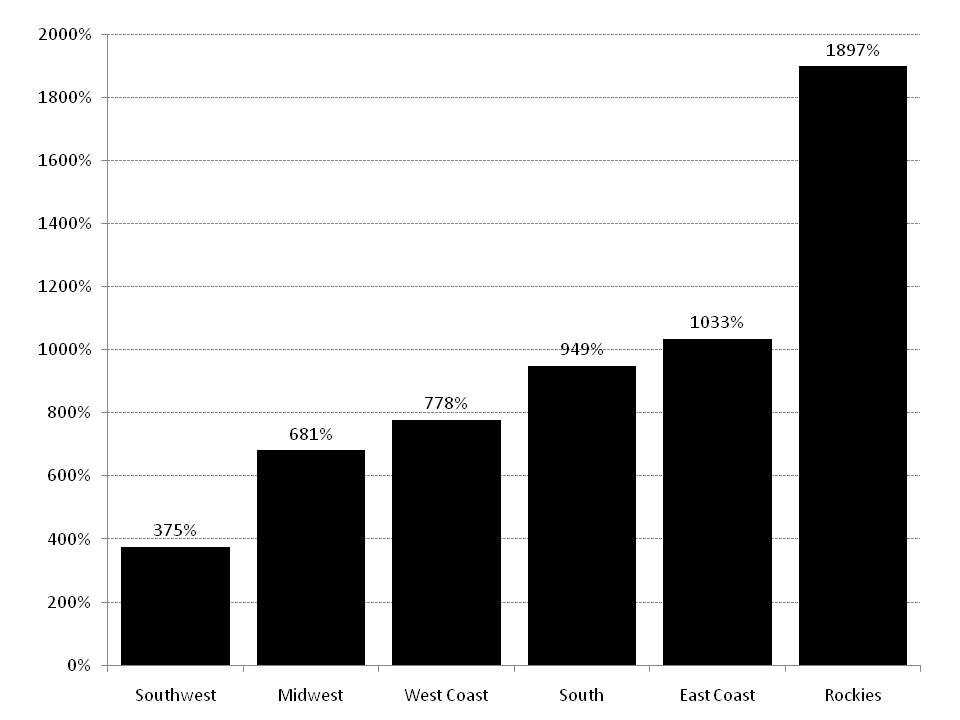

Between 2000 and 2010, U.S. exports to China rose from $16.2 billion to $91.9 billion. This 468% increase far outstrips the 55% rate that U.S. trade with the rest of the world grew at over the past decade. The West Coast, which enjoyed 778% growth in its exports to China over the past decade, remains the powerhouse of U.S. exports to China, accounting for 30% of total U.S. exports to China in 2010. However, the East Coast, which now provides nearly 20% of U.S. exports to China, saw its exports to the Middle Kingdom rise by more than 1,000% between 2000 and 2010 (Exhibit 1). Exports from southern states (18% of total US exports to China) boosted their sales to China by 949%, midwestern exporters (12% of total) increased exports to China by 681%, and the southwest, anchored by Texas and Arizona, expanded exports to China by 375% and now accounts for 13% of U.S. exports to China.

Exhibit 1: Growth of U.S. exports to China by region, 2000-10

Source: USCBC, China SignPost™

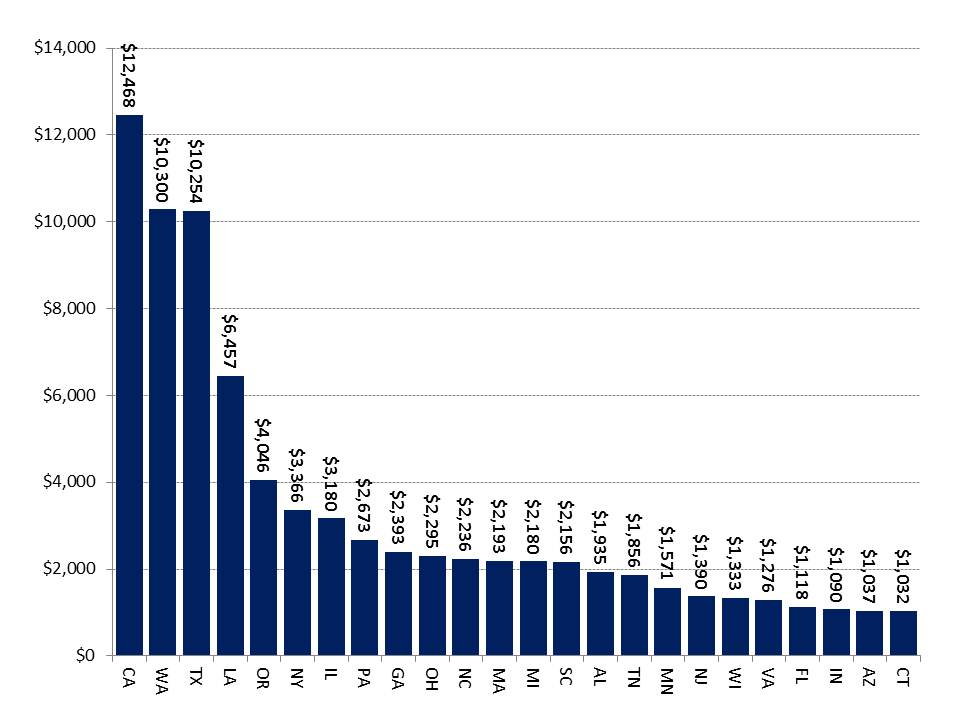

Twenty four states each exported more than $1 billion worth of goods to China in 2010, a sharp rise from the seven states that exceeded that level in 2005 (Exhibit 2). Key items include agricultural products and foods, machinery and transport equipment, chemicals, raw materials and scrap, and hi-tech goods. Interestingly, Rust Belt states that have been hit hard by migration of industrial activity overseas have been major beneficiaries of China’s growth as a market for U.S. exports. China was the number three export destination for Ohio and Michigan after NAFTA members Canada and Mexico in 2010, while China was Pennsylvania’s second largest export market.

The growing geographical diversity of U.S. exports to China has important political ramifications. Many areas hardest hit by the economic downturn—such as the Rust Belt and Midwest—are also seeing rapid growth in exports to China, which may actually toughen the stances that members of Congress from those regions take regarding China’s currency valuation, for example, because continued RMB appreciation helps make U.S. exports to China more competitive.

Exhibit 2: U.S. states with $1 billion or more of exports to China in 2010

Million USD

Source: USCBC, China SignPost™

At the same time, Chinese interest in investing in economic assets in depressed areas of the U.S. may increase, particularly if the facilities in question have unrealized value for producing automotive and other equipment for export to China, or markets in Latin America that are growing faster than the U.S., and which can be advantageously supplied from U.S.-based plants. Chinese investors may also go bargain hunting in U.S. real estate markets and also consider acquiring farmland to produce grain for export to China or sale in local markets.

Established exporters to China, such as California, Washington, and Texas saw their exports to China grow by 252%, 442%, and 606%, respectively between 2000 and 2010. Other states not previously thought of as China trade powerhouses, including Oregon, Ohio, Michigan, Louisiana, Georgia, and Alabama saw their exports to China expand by between 507% and 1,227% during the 2000 to 2010 period.

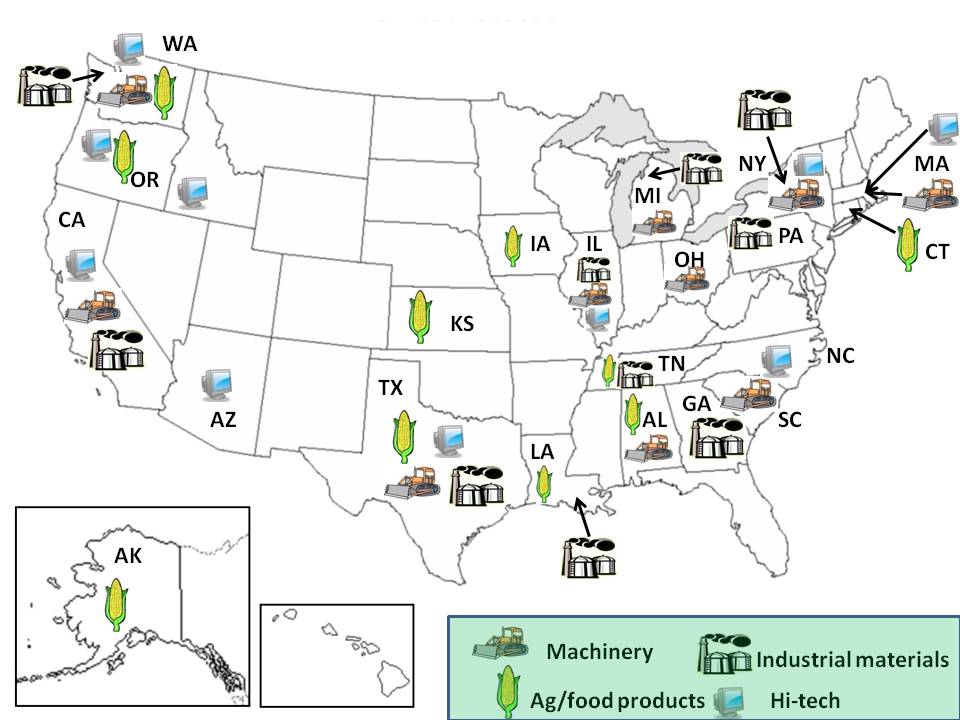

Exhibit 3 shows the locations of the top 10 state exporters of agricultural products and foods, machinery and transport equipment, chemicals, raw materials and scrap, and hi-tech goods, in order to give readers a better feel for the growing regional diversification of U.S. exports to China.

Exhibit 3: Locations of the 10 largest U.S. exporters to China by product category

Source: USCBC, China SignPost™

One word of caution in assessing the level and type of a particular state’s exports to China is in order. The data reporting system used for reporting U.S. exports to China by state may inadvertently inflate the apparent exports of states that are home to large ports. For example, we note that the agricultural exports of Louisiana and Washington were $4.7 billion and $4.0 billion, respectively. As such, the large size of the dollar amount is likely due to the fact that these two states have major grain exports ports and that the figures actually reflect in part the value of grain grown by the large Midwestern producers like Iowa and Illinois, and then shipped to China through Gulf Coast and Pacific ports.

Implications

As the U.S. exports more goods to China, a number of key questions arise. One is how to increase the U.S. share of China’s total imports, which despite the strong growth in absolute dollar terms has actually fallen from 10% in 2000 to 7% in 2010, according to USCBC. Federal policies can be helpful for promoting exports, but state-level approaches to prospective importers in China and Chinese investment partners may actually be a more effective approach, as it can be more focused and less impeded by national political friction points like currency valuation.

The second question concerns identifying how to maximize American exports’ access to the Chinese market. Agricultural products, the second largest export in 2010, are driven by the fact that China is close to exhausting its water and arable land supplies in many grain growing areas, and changes in the diet that favor grain-intensive protein items like meat and eggs.

U.S. exports of agricultural and food products to China are well positioned to grow strongly. U.S. agricultural exports to China are dominated by soybeans (~80% of exports), but there is substantial room to expand exports of other grains like corn, as well as pork and beef, if China can be persuaded to remove the substantial regulatory barriers that now impede meat imports from the U.S.

Other items such as hi-tech goods and transportation equipment and other machinery are also well-positioned for further growth in exports to China. However, they face much higher risks of being reverse engineered by Chinese competitors who may then be able to sell products at lower prices and thereby undercut U.S. export markets for these items. In the longer-term, the aerospace industry is likely to face pressure to conduct more assembly operations in China and eventually, China’s domestic manufacturers will be able to compete with Boeing on a high enough level that Chinese aircraft buyers turn more toward domestically made aircraft. This is not to say “don’t export to China,” but it does suggest that tighter safeguards regarding sharing of key technology and industrial process know-how deserve careful scrutiny and regulatory vetting.