Current situation

Libya’s security situation is becoming increasingly volatile as embattled leader Col. Muammar Gaddafi faces an increasingly capable set of opposition forces. Anti-government forces have been bolstered by the decision by most of Libya’s 80,000-strong armed forces to lay down their arms, according to the Globe and Mail. Anti-government forces are also capturing territory in western Libya, Gaddafi’s traditional regional stronghold, and are now deploying tanks and other heavy weapons, reports the Los Angeles Times.

We project that if Gaddafi indeed attempts to retain power until the end, the stage will be set for high-casualty confrontations between pro- and anti-regime forces, which are becoming ever-more-evenly matched. Chinese remaining in Libya risk getting caught in the crossfire. China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) says that while its 391 employees in country are all safe, some of its oil facilities there have been attacked. Against this volatile backdrop, the desire of China and other countries to deploy military platforms to oversee the evacuation of citizens still trapped in Libya is highly understandable. Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Song Tao says that as of 25 February, 12,000 of the ~30,000 Chinese citizens in Libya had been evacuated by chartered planes, ships, and buses (Xinhua).

To ensure a reliable backstop to these continuing operations in accordance with Beijing’s robust conception of national sovereignty, China’s navy is conducting its first-ever operational deployment to the Mediterranean. It is designed specifically to safeguard evacuation operations in uncertain conditions, to ensure that Beijing has a voice in critical regional issues, and to help guarantee that China’s government is seen as capable and competent both at home and abroad. As Qu Xing, president of the China Institute for International Studies, told China Central Television (CCTV): “No matter what kind of attitude the foreign media are having when seeing China, they will have to agree that China has the efficiency, power, and mobility to handle such activities.”

Tracking China’s Xuzhou warship

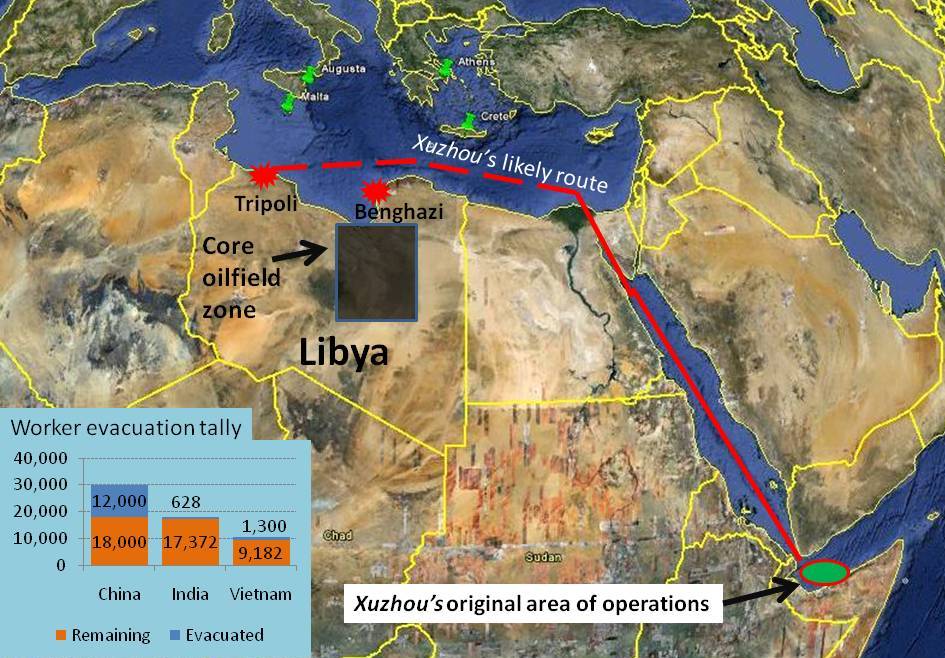

China’s Type 054A Jiangkai-II Class guided-missile frigate Xuzhou (Hull 530) passed through the Suez Canal and entered the Mediterranean Sea on 27 February 2011, according to Sohu. Exhibit 1 (below) shows the approximate route Xuzhou is likely to take, as well as focal points for Chinese interests in Libya and worker evacuation figures for some of Asia’s larger countries with workers in Libya. The Sohu article claims Xuzhou will enter waters near Libya on Wednesday 2 March 2011. This arrival time suggests that Xuzhou will be steaming at roughly 30 km per hr (16 knots), in line with Xuzhou’s cruising speed, which Jane’s reports as roughly 33 kmph (18 knots). Xuzhou left the Omani port of Salalah on 28 January 2011 after a 5-day replenishment and overhaul visit to rejoin the anti-piracy task force in the Gulf of Aden, according to CCTV. This suggests that the ship will be in good mechanical shape for its support mission off Libya.

Refueling will be a key issue for deployment sustainability, particularly if the Libyan crisis is prolonged and Xuzhou is forced to remain on station longer. Jane’s claims the vessel has a range of just over 7,000 km (3,783 nautical miles). As of 16 February 2011, Xuzhou was operating near the mouth of the Red Sea, where it dispatched three special operations force personnel in a helicopter to chase pirates away from a South Korean merchant vessel (PLA Daily). The distance from the mouth of the Red Sea to the waters off Tripoli is approximately 4,500 km (2,432 nm), so Xuzhou will likely have used at least 2/3 of its fuel by the time it reaches the area of operations off Libya’s coast, absent replenishment en route.

We believe that the Italian port of Augusta (Sicily), Malta, and Crete all offer potential bunkering locations for Xuzhou to refuel. These ports are indicated with light green markers in Exhibit 1.

Exhibit 1: Xuzhou route map and worker evacuation tally as of 27 February 2011

Source: Sohu, Reuters, Mumbai Mirror, The Economist, World Ports, China SignPost™

Xuzhou is one of China’s most advanced frigates. It participated in China’s first international naval fleet review in Qingdao in April 2009, and has already made the long journey from its East Sea Fleet homeport of Zhoushan, from which it sailed to the Gulf of Aden in July 2009 to participate in China’s third Gulf of Aden task force. On 2 November 2010, it left with frigate Zhoushan and supply ship Qiandaohu, two shipborne helicopters, and dozens of special forces personnel to participate in the still-ongoing seventh task force, which arrived in the Gulf of Aden on 17 November.

Implications

What a difference twenty years makes. In 1991, civil war in Somalia forced embassies and consulates, including China’s (in Mogadishu and Kismayo, respectively), to evacuate their personnel. Lacking relevant naval assets, Beijing relied on state-owned China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO) for support. As a recent National Defense University study documents, COSCO diverted the cargo ship Yongmen, then sailing from Europe through the Gulf of Aden, to rescue the Chinese personnel.

Large evacuee numbers, lack of charts and experienced crew, inadequate raft capabilities, rough seas, and insecurity pierside forced Chinese operators to hire two local tug boats to transport personnel from Mogadishu’s pier to Yongmen. Kismayo’s small port could not accommodate Yongmen, forcing the hiring of a large fishing vessel and a tug to effect a similar personnel transfer. Moreover, Yongmen had to sail to Mombasa, Kenya to drop off each city’s personnel separately, thus further prolonging the operation.

Almost exactly two decades later, China finally has the capability to evacuate its citizens rapidly, including from inland locations, and to safeguard such evacuations with some degree of military force. China’s present urgency to evacuate its nationals from Libya suggests that Beijing recognizes the potential for significant additional bloodshed in Libya as anti-regime forces gain strength and Gaddafi and his supporters fight to remain in power.

We think the crisis also shows that China’s leadership is becoming increasingly sensitive to nationalist pressures to protect PRC citizens threatened by crises overseas. Given that Xuzhou was near the mouth of the Red Sea, it likely faced a voyage of roughly 2,500 km to reach the Mediterranean Sea. At a cruising speed of 33 kmph (18 knots) plus 1 day to transit the Suez Canal, we estimate that the total voyage time was ~4 days. Only two days separated the first public announcement of the Central Military Commission’s decision to send Xuzhou to Libya and the announcement that it was ready to enter the Mediterranean. To us, this suggests that Beijing was considering deploying the ship earlier than publicly announced. In a possible sign of growing policy consensus in favor of such missions, PLA National Defense University professor Major General Ji Mingkui told the official China Radio International on 25 February: “With non-security missions … increasing, our navy’s participation in the evacuation of overseas Chinese people [during crisis] is just one of their tasks. We will not only dispatch warships to evacuate our people overseas [when needed] in future, but in other ways … to protect our national interests overseas because our navy’s missions will be expanded as time goes on.”

China’s navy has used the anti-piracy deployment to the Gulf of Aden to develop a regional network of ports in Oman and other countries where its vessels can refuel and replenish. If the Libya crisis persists long enough and Xuzhou refuels and replenishes in the region, the PLA Navy will be able to strengthen its port access abilities in the Mediterranean as well. In the event of violence that reaches a high enough level to significantly impair the evacuation operation, a worst case scenario could force Beijing to authorize the use of Xuzhou’s anti-air, anti-surface, embarked special forces, and helicopter capabilities, and even to consider sending additional military assets to the region. Despite its unprecedented naval presence and capabilities, however, China is likely to use its military forces in the Mediterranean only as a deterrent and a selective logistics facilitator, and to maintain its preferred soft-power approach of using diplomatic, information, and economic means to further its interests wherever possible.

Correction: Initial wording in this report did not make it clear that we expect Xuzhou to “reach waters near Libya,” and to not actually enter Libya’s territorial waters (from shore to 12 nautical miles) without Libyan permission, unless dire circumstances warrant otherwise. This is in keeping with the “robust conception of national sovereignty” on China’s part that we mentioned originally. The phrase in question has now been corrected in both the PDF and HTML versions of this document.

Additional analysis on China’s interests in the Libya crisis and protecting its citizens overseas:

For more details on Beijing’s dispatching of the frigate Xuzhou to escort ships transporting Chinese citizens from Libya, see Gabe Collins and Andrew Erickson, “China Dispatches Warship to Protect Libya Evacuation Mission: Marks the PRC’s first use of frontline military assets to protect an evacuation mission,” China SignPost™ (洞察中国), No. 25 (24 February 2011).

For analysis of Beijing’s interests in Libya and the surrounding region, see Gabe Collins and Andrew Erickson, “Libya Looming: Key strategic implications for China of unrest in the Arab World and Iran,” China SignPost™ (洞察中国), No. 24 (22 February 2011).

For early projections regarding Chinese efforts to protect citizens overseas, see Andrew Erickson and Gabe Collins, “Looking After China’s Own: Pressure to Protect PRC Citizens Working Overseas Likely to Rise,” China Signpost 洞察中国™, No. 2 (17 August 2010).