–Famine and grain supply problems helped topple at least 5 of China’s 17 dynasties.

–Global grain prices are already near the 2008 levels that sparked food riots in some countries, and continue to rise.

–The Chinese government has already pledged nearly US$2 billion to fight drought in China’s wheat producing North, where 42% of the crop area is currently affected by drought.

–Combating food price inflation will likely remain a major policy priority for Beijing throughout 2011.

Global corn prices are at 30-month highs due to strong demand, falling stockpiles, and robust ethanol demand in the U.S. Wheat prices are likely to rise further, owing in part to drought in major producers. China’s Ministry of Agriculture says that as of early February 2011, 42% of the crop area in 8 main wheat-growing provinces was being affected by drought. Premier Wen Jiabao says the government is prepared to spend nearly US$2 billion to help farmers combat the drought.

Food security problems have particular resonance in China due to the country’s size, population, and the role that famine has played in fomenting political unrest. Indeed, to this day the government provides very large subsidies to farmers to try to keep the country self-sufficient in grain production. The upper echelons of the Communist Party likely have a deep-seated historical consciousness of how bad things can become if food supplies falter and clearly want to keep inflation under control and maintain stable economic growth in the run-up to the 2012 Party Congress and transition of power from President Hu to his successor Xi Jinping.

Throughout China’s history, food shortages caused by natural disasters such as drought and flooding have often catalyzed rebellion or compounded existing turmoil that toppled dynasties. Parched fields, empty granaries, and famine meant the emperor had lost the Mandate of Heaven and had to leave power. In short, when food becomes scarce in China, the risk of chaos and violent transitions of political power rise sharply.

Recent academic studies support this view. A team of Chinese and European scientists led by Zhibin Zhang of the Chinese Academy of Sciences published a study in 2010 which concludes that “The collapses of the agricultural dynasties of the Han (25-220), Tang (618-907), Northern Song (960-1125), Southern Song (1127-1279) and Ming (1368-1644) are closely associated with low temperature or the rapid decline in temperature.”

Low temperature periods are typically associated with rising desertification in China and lower crop yields, which often triggered famines. Warmer times, in contrast, were often marked by better crops, greater stability, and dynastic expansion. The researchers also note that in their analysis rapid increases in rice prices and locust plagues, both of which reflect grain supply shortfalls, were among the most powerful drivers of dynastic collapse. Our research yields similar results. Of 17 major dynastic periods, famine played a major role in catalyzing dynastic declines and collapses in 5 instances: the Xin, Han, Tang, Yuan, and Ming dynasties.

We note that these events marked some of the biggest famines. More localized famines that nonetheless enacted a terrible human toll afflicted the country much more frequently. In his book The Troubled Empire, Timothy Brook notes that during 350 years of rule by the Yuan and Ming Dynasties, at least 9 major famines beset China. Brook says that during the Yuan Dynasty, there was a major famine somewhere in China every two years on average.

Maintaining steady and sufficient food supplies is a key pillar of Communist Party legitimacy. Indeed, Dr. Felix Wemheuer’s new edited volume, Eating Bitterness, emphasizes that when the Communist Party came to power, Mao Zedong declared that “not even one person shall die of hunger.”

With the exception of the tragic Great Leap Forward, famine concerns in China over the past 70 years have not centered on true grain scarcity that leaves people eating straw, rodents, or anything else they can find. Rather, it has been an issue of rising prices that render grain inaccessible to the poorer segments of the populace and make food prices a major burden for others. Food is a significant expenditure for many Chinese, which is why the Chinese government constantly worries about keeping inflation in check. The Nationalists’ inability to control inflation helped sway urban Chinese to support the Communists after World War II, while rising inflation was an important contributing factor in many Chinese workers’ decisions to support the protesters in Tiananmen Square in 1989.

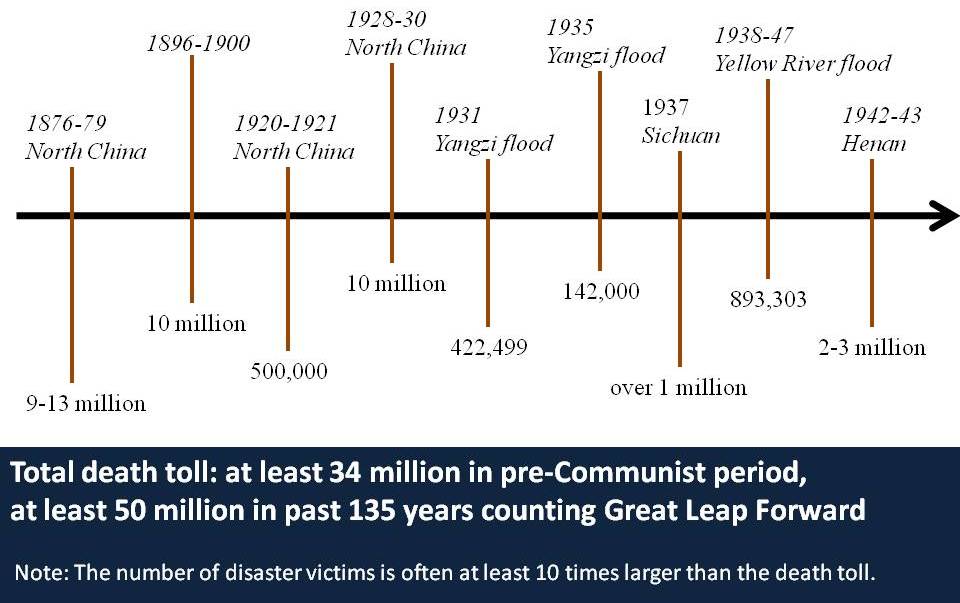

Exhibit 1: China Famine Timeline, 1876-1943

Source: Felix Wemheuer, China SignPost™

Implications

Famine or food supply problems pose a significant challenge for any Chinese leadership, but do not always lead to political downfall. Indeed, dynasties often endured for hundreds of years despite the regular incidence of regional famines noted above. Unlike their imperial predecessors, moreover, China’s present leaders now have a range of capabilities at their disposal to mitigate grain shortages and to handle localized grain shortages that would have caused great suffering in earlier times.

The country’s rail system allows grain to be moved to distant points around the country within days. China can also import corn, wheat, and other staples from the international market and suspend or reduce grain import duties if necessary. China now holds approximately 200 million tonnes of grain stockpiles, according to a recent article in China Youth Daily. This is equivalent to more than 40% of annual grain demand—significantly higher than the oft-cited “safety level” of 17-18% of demand.

That said, in an era of cell phone text messaging, QQ instant messaging, and other mass communications tools, discontent with high food prices or even temporary disruptions in grain supplies have the potential to create far more profound political effects than would have been the case even in the 1870s, when a great famine likely killed more than 10 million people in North China, according to University College Dublin historian Cormac Ó Gráda.

The danger of a true famine in China is low and would require a disaster of global proportions to become conceivable. Yet high inflation caused by skyrocketing food prices remains a significant risk for Beijing to manage, as high food prices are a powerful catalyst of social unrest. High grain prices will be a tough challenge for China’s leaders throughout 2011 and we expect further decisive action as Beijing tries to fight powerful market forces that are making staple grains tougher for consumers to afford.

China Youth Daily depicts a weak and disorganized domestic grain supply chain and advocates vertical integration in the grain industry by creating a number of large, Sino Grain-type firms to protect China’s national food security interests from foreign corporations that (in that author’s view) put profits before people’s wellbeing. China will welcome grain imports as needed, but if such sentiments spread, foreign investors who actually wish to produce and process grains within China may find additional regulatory barriers in their way.